The Story

Water use per person decreases by 15% from today’s levels, which is 25% less than what was used in 2000. To supply water to our growing population, we build local water projects (wells, tanks, treatment plants, pipelines, efficiency improvements, etc.). We also build the Lake Powell Pipeline to serve southwestern Utah and the Bear River Project to serve the Wasatch Front. These projects use Utah’s remaining rights to the Colorado and Bear Rivers. A significant amount of our water also comes from agricultural lands that are replaced by homes and businesses as our communities grow. By 2050, sufficient water will be either developed or taken from other uses to satisfy new demands and to provide some reserve capacity for protection against droughts.

Water use per person decreases by 15% because:

- Businesses use about 15% less water per job than today.

- We use 15% less water indoors and outdoors.

- Landscaping in yards and public open space use a maximum of 50% grass.

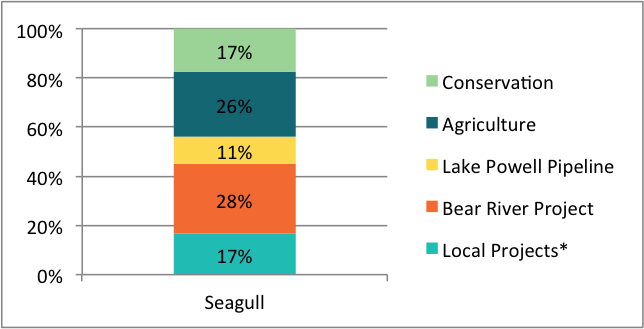

Where the Additional Water Comes From

* Projects such as wells, tanks, and treatment plants

Results

- Annual cost to install and maintain the average yard is $1,850 (increase from today’s $1,700), and portions of many existing lawns need to be replaced with low-water plants and drip irrigation, at some expense.

- Cost per household for new infrastructure is $6,700 spread over 35 years.

- Relatively low costs for conservation are either borne directly by homeowners (replacing lawns, etc.) or incurred by water providers and added to water rates.

- Agricultural production decreases by 8% statewide.

- More diverse water sources provide some reserve capacity for protection against drought or climate variability.

- During droughts some water can be taken from yards to meet critical needs.

- Water withdrawals and loss of natural habitats in the Colorado, Bear, and local river systems continue.

Typical Landscape

Background

Utah remains the second driest state in the nation. Adding another 2.5 million people requires careful planning and hard choices about providing water for expanding cities and towns, business growth, growing food to feed more people, and the environment. More water for more people can come from: (1) conservation; (2) local projects such as wells, tanks, treatment plants, and pipelines to move water now used to supply farms or sustain our natural environments; and (3) larger projects that would divert water from the Bear and Colorado Rivers. Because these two rivers flow through multiple states, the states have entered into compacts that divide the waters among them. Though questions remain about cost and sustainability, particularly given existing demands on the Colorado River, developing the Lake Powell Pipeline and the Bear River Project would allow Utah to use the water allocated to it through these interstate compacts.

Most of our State’s water supplies cannot be shared between basins or even between municipalities. This means, for example, water development and conservation in Central Utah will not create additional water for the Wasatch Front. All water development projects, conservation methods, and water needs must be evaluated on a local and regional scale to ensure that each Utah resident and business will have sufficient water now and in the future and that our natural environments will thrive so that Utah continues to be a great place to live.

Reducing the amount of water that we use in homes, on our landscaping, and in our businesses can delay our need for new development projects. We currently use about 240 gallons per person each day for our homes, yards, and businesses. Governor Herbert has set a statewide goal to use 25% less water per person by 2025. We have made significant strides in reaching this goal. Most areas of the State are already conserving 15% or more since 2000 when the goal was set. In southern Utah, conservation levels have reached as high as 35%. We can further reduce our water use in several ways:

- Design smaller lots in new subdivisions.

- Replace grass with plants, shrubs, and trees that require less water.

- Implement more efficient watering techniques (e.g., drip irrigation or sprinkler timers that adjust for weather).

- Introduce additional low-flow fixtures in homes and businesses.

- Reduce waste (e.g., don’t water during the afternoon, etc.).

- Expand the use of tiered pricing structures that increase water rates, when more water is used, to encourage conservation.

Water conservation is not free and in certain circumstances may be very expensive. There are costs associated with education campaigns, landscape and irrigation system changes, new fixtures, incentive programs, etc.

The effect of conservation on natural environments must be determined on a case-by-case basis. In some circumstances, it can reduce withdrawals from streams, improving downstream habitat. Conservation can also reduce how much water returns to streams, harming water bodies that have come to rely on those flows.

Some water for communities will likely come from agricultural land that is sold and developed as locations for new homes and businesses. When agricultural lands are sold for development, the city in which the development occurs typically acquires the water rights. If we continue to grow as we have over the past twenty years we will consume almost 10% of our remaining agricultural lands by 2050, much of it prime farmland for fruits and vegetables along the Wasatch Front. This will further erode our ability to provide the food necessary to a growing population. In addition, some agricultural water may be expensive to treat for culinary use.

As we plan for growth and our water supply, we must also plan for periods of drought and climate variability. Utah frequently experiences droughts that last for years. Climate models from Utah State University predict that northern Utah may become warmer and that more of our precipitation will fall as rain instead of snow. Because snowpack provides a significant portion of our water storage, this could dramatically reduce overall water storage. If this happens, we will not be able to build enough reservoirs to replace the lost snowpack storage. Maintaining healthy watersheds to absorb and slowly release that water will become increasingly critical. Those same climate models predict that southern Utah could become warmer and drier.